Triple Fusion Anniversary

back to contentsIt was 60 years ago, in March 1965, that a tokamak named T-6 was put into operation. Its upgraded version T-11 was commissioned 50 years ago. T-11 was further modified and is still in operation at the Troitsk Institute of Innovative and Thermonuclear Research (TRINITI), where it is used to pilot advanced solutions for nuclear fusion technology.

As it is obvious from the name, T-6 was not the first or the last tokamak built. By the way, the first discussion of using controlled thermonuclear fusion (CTF) for commercial power production also has an anniversary this year. It was 1950 when a young sergeant Oleg Lavrentiev, who was then doing his military service on Sakhalin, wrote a letter to the Central Committee of the Soviet Union Communist Party. The letter outlined two ideas, one of which was devoted to CTF. Oleg Lavrentiev proposed a reactor design isolating high-temperature plasma with a high-voltage electric field. The letter was passed on to nuclear physicists, and they noted the originality and boldness of the author’s idea.

A more viable idea of a toroidal fusion reactor with magnetic plasma confinement was proposed by Andrey Sakharov and Igor Tamm, and approved in January 1951. The first installation was assembled the same year. It was a glass torus in a thick-walled copper casing. Researchers assumed that plasma would be heated by the current flowing through it and kept away from contact with the walls by eddy currents induced in the copper casing. Later, in 1957, Igor Golovin, a student of Igor Kurchatov, proposed to name the CTF system developed by Soviet scientists a ‘tokamak’. This word is short for Russian ‘toroidal chamber with magnetic coils’.

The toroidal concept competed with the stellarator concept at that time. An international CTF conference held in Novosibirsk in 1968 added clarity to the matter: Soviet scientists reported on the experimental results achieved on tokamaks, and they were orders of magnitude better than those obtained on other types of facilities. Figuratively speaking, their reports turned out to be an intellectual ‘thermonuclear explosion’.

After that, tokamaks were built in many countries around the world, taking a leading position in the field of thermonuclear research. The USSR alone built 21 tokamaks in 1960–1988, and some of them were moved to other countries. What is more, the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), which is designed to prove the possibility of commercial thermonuclear fusion, is also a tokamak.

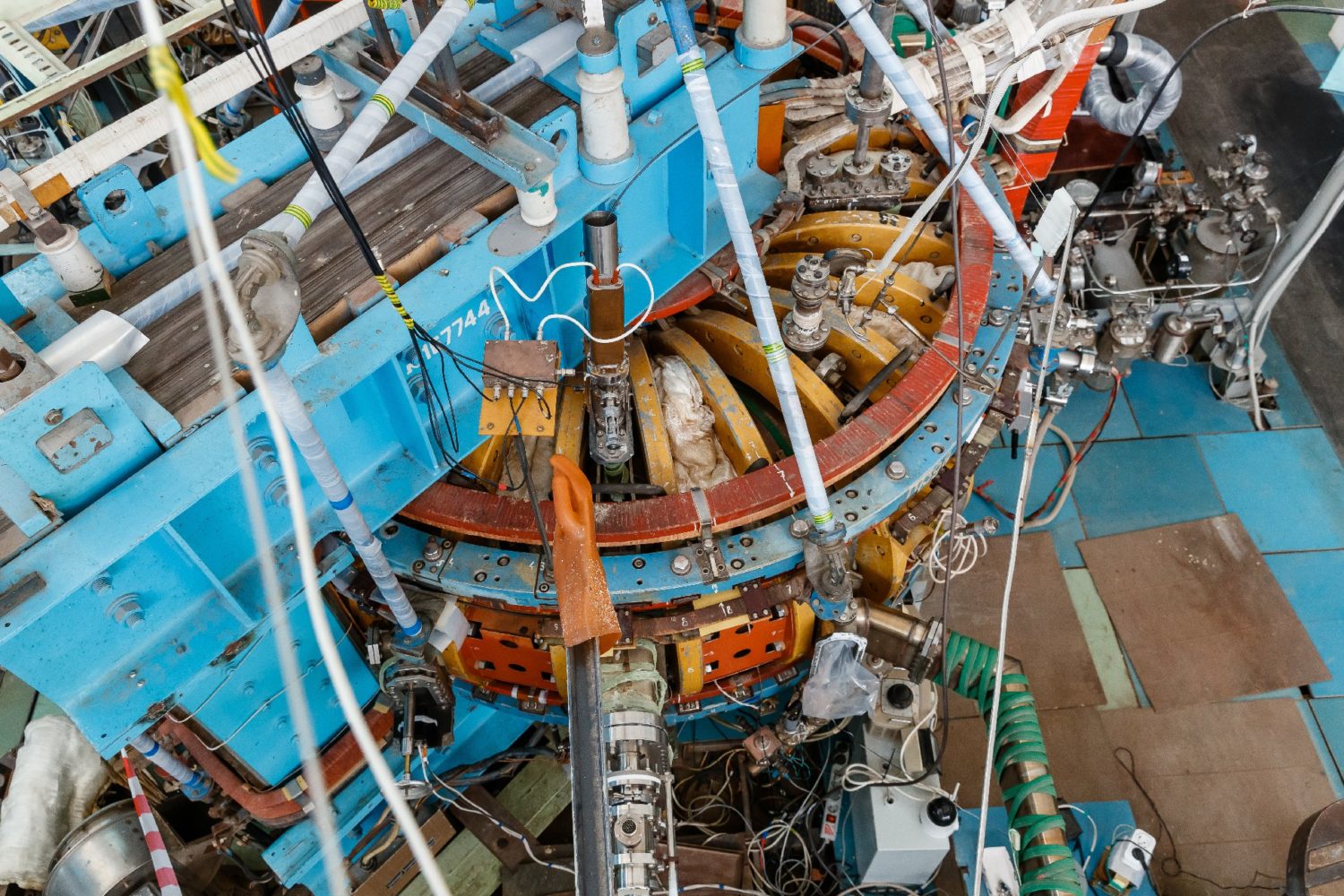

The T-6 tokamak unit was designed by Vladimir Mukhovatov, a junior researcher at the Kurchatov Institute and a future winner of the USSR State Prize. The T-6 installation was conceived by him as capable of generating an extremely smooth (non-corrugated) toroidal magnetic field. T-6 had a stabilizing copper casing inside the discharge chamber, ultimately close to plasma, for the installation to operate at maximum currents and minimum stability margins. It was used to study plasma stability in detail.

In 1975, the unit was upgraded and named T-11. The upgraded tokamak was used to hold experiments on additional plasma heating by injecting a beam of fast neutral atoms. This was important because additional plasma heating in tokamaks had become a new challenge by that time. Calculations showed that the maximum plasma temperature that could be achieved by conventional heating is 4 to 5 times lower than that required for an intensive thermonuclear reaction. The idea of injecting neutral atoms showed good results.

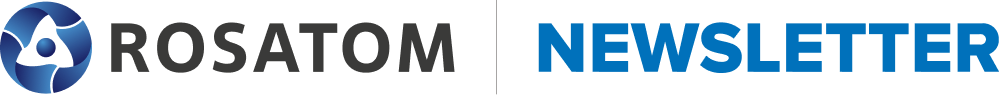

In 1985, the tokamak was dismantled, then retrofitted and, thanks to the efforts of a famous Russian physicist E.A. Azizov, re-installed under the name T-11M to solve diagnostic tasks. T-11M at TRINITI is currently one of the three magnetic plasma confinement facilities operating in Russia. It serves as a facility for studying materials that can solve the so-called ‘first wall’ problem, and test their potential as plasma-facing materials in real conditions.

The first major success is the use of carborane as a boronization material for the first wall of all Russian and some foreign tokamaks in order to reduce the level of impurities. The second success is the use of lithium and capillary porous systems for the same purpose.

By modern standards, T-11M is quite modest in terms of performance, with plasma current of up to 0.1 MA, plasma electron temperature of up to 500 eV and maximum plasma density of 7 x 1013 cm3. This is enough, though, to study plasma interactions with the tokamak first wall and first wall materials, develop the means of first wall protection, study plasma disruption processes, and pilot new plasma diagnostic methods.

Currently, liquid lithium shielding for tokamaks is being developed at T-11M. The shield is needed to catch particles coming from plasma, thus reducing the thermal impact on the wall. In 2022, TRINITI researchers managed to fill the T-11M emitter system with lithium from outside without de-vacuumizing the chamber, which is a world-class result.

T-11M is now being used to test the full set of lithium protection systems and equipment for the fusion reactor first wall, including such promising devices as limiters, collectors, and injectors.

The results of tests and research at T-11M, particularly liquid lithium protection and boronization with boron carbide techniques, are used at more complex facilities, such as T-15MD and reactor technology (RTT) tokamaks, and in the ITER project. Liquid lithium protection is planned to be used at the RTT.

Photo by: newspaper “Strana Rosatom”