I’ll be back-end

back to contentsDelegates from the CIS countries discussed nuclear legacy management, handling of radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel, and government regulation in this area at a conference organized by Rosatom in August. Russian expertise attracted the greatest interest as the country has followed a comprehensive approach to nuclear waste management since 2011. Rosatom is willing to share its knowledge and best practices with its counterparts from Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and other countries.

Russian expertise

“We can handle radioactive waste and know how to safely isolate it. We are ready to share our knowledge and expertise with the countries to whom our solutions might prove essential,” Marina Belyaeva, Director for International Cooperation at Rosatom, said at the conference opening.

Russia pursues a comprehensive approach to the infrastructure for radioactive waste management and final isolation. First, a legal framework was established as the government passed a law on radioactive waste management in 2011 and authorized one of Rosatom’s divisions to act as a national operator for radioactive waste management (NORWM) in 2012. New regulations were enacted to establish classification criteria and disposal procedures for different radioactive waste categories.

Today, nuclear waste has owners. As Alexander Baryshev, Deputy Chief Operating Officer at NORWM, said at the conference, the waste existing before 2011 is owned by the government while the waste produced afterwards is owned by its producers. This division determines financial obligations. The government pays for legacy waste, and producers pay for the new waste they generate. All the owners make quarterly payments to a dedicated public fund.

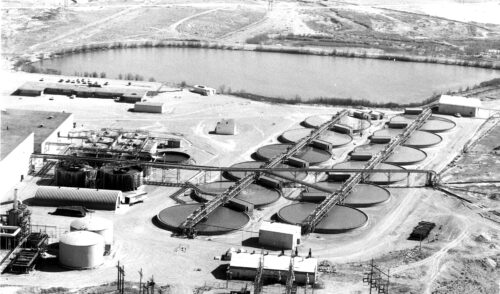

The money collected is allocated to build and maintain necessary infrastructure (radioactive waste repositories). In 2016, the first section of a near-surface repository near Novouralsk was put in operation, followed by the second section this spring. Similar disposal sites are constructed in the Chelyabinsk and Tomsk regions to be commissioned by 2026.

Alternative options of nuclear waste isolation are also explored. In the late 2020s, site surveys will be carried out to establish a long-term safety case for a deep geological repository planned to be built in the Nizhnekansky massif (Siberia). The final decision to this effect will be made in the mid‑2030s. Until then, class 1 and class 2 (medium and high level) radioactive waste will continue to be stored at the Mayak site in the Chelyabinsk region.

Other countries

Delegates from the CIS countries also shared their experience and plans for the future. For instance, Kyrgyzstan conducts remediation activities at its closed uranium mining sites. The scope of work includes cleaning of debris-flow and water drainage channels and ditches, restoration of the protective layer on tailing pond dams, reinforcement of protective structures, and so on. In Tajikistan, remediation of legacy uranium mines is also in progress. Kazakhstan converts its research reactors from high to low-enriched nuclear fuel and decommissions some of the nuclear facilities operated by MAEK-Kazatomprom, the most important of which is the BN‑350 fast neutron reactor. All in all, there are more than 40 legacy sites in the CIS countries that need remediation.

TVEL, Rosatom fuel division, proposes to set up ranking criteria to prioritize nuclear legacy sites. The criteria will be based on technical data, broken down by categories (environmental impact, social impact, human safety, and radioactivity) and assigned scores.

“It is one thing if there have been no accidents on the site, reservoirs are intact, and there is some service life left so that the equipment remains operative. It is another thing, though, if there have been spills or contaminations outside of the control area. Community factors may also come into play. For instance, the site can be relatively safe but local residents have a clearly negative attitude to it. Costs are no less important: if two different sites pose the same level of threat but decommissioning one of them is more expensive, it might be reasonable to start with the less costly one,” explains Eduard Nikitin, Director of Nuclear Decommissioning Programs at TVEL. It is not an easy task to squeeze the variety of factors into a rigid set of criteria but it will not be possible otherwise to assess which site needs remediation first, he added.

Harmonization of law

Approximation and harmonization of national legislations in the CIS is another essential task. For now, national regulations use different classification criteria for radioactive waste. “Radionuclides are, however, the same anywhere in the world, so it would be logical to standardize classification rules,” Eduard Nikitin noted. Some agreements to this effect have already been reached.

As a major CIS company engaged in nuclear legacy management, TVEL proposed that the CIS countries draft a model law on radioactive waste management and nuclear decommissioning to harmonize their national legislations.

The law is planned to be based on international conventions, IAEA guidelines, and agreements signed by the CIS countries. Russian laws and regulations will also be taken into account. Thanks to the expertise gained, they are best suited to regulate nuclear decommissioning and remediation activities.

IAEA

TVEL shares its back-end experience not only with the CIS countries, but also with the international community. In a series of technical meetings organized by the IAEA in August, TVEL experts presented their reports on staff training and decommissioning of research reactors, including fast neutron reactors. These are research reactors MR and RFT at Kurchatov Institute and BR‑10 at the Institute of Physics and Power Engineering (part of Rosatom).