Money for Atoms

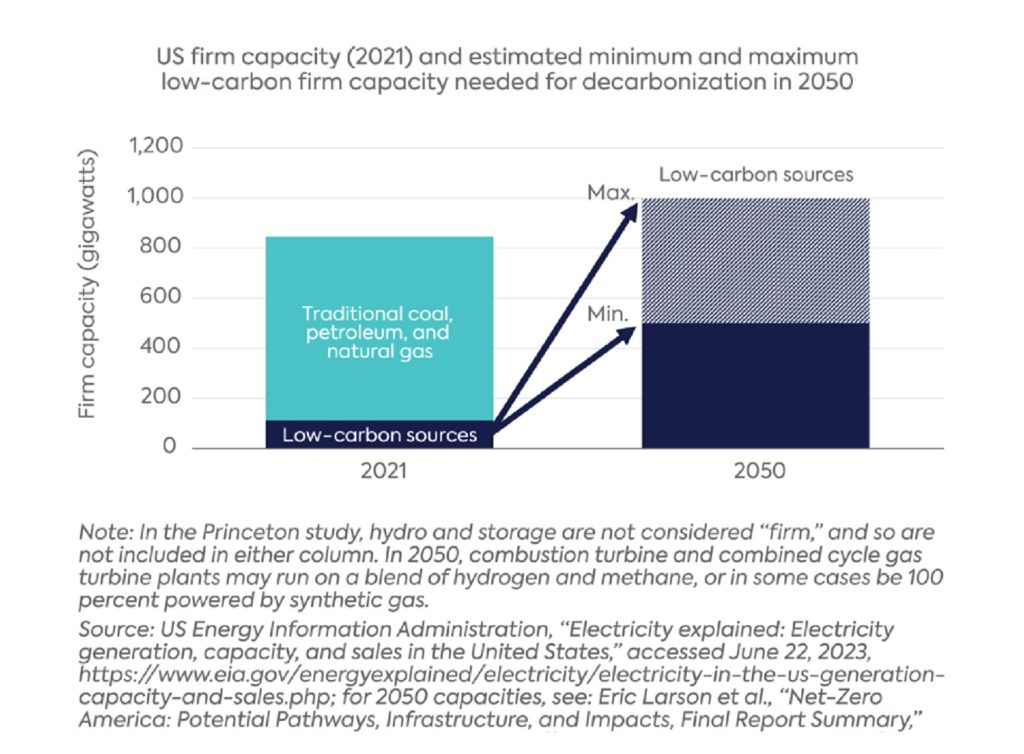

vissza a tartalomjegyzékhezThe Center on Global Energy Policy (CGEP) at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs published a study titled “A Critical Disconnect: Relying on Nuclear Energy in Decarbonization Models While Excluding It from Climate Finance Taxonomies”. The study’s central idea is that institutional investors drag their heels on investing in nuclear energy although its crucial role in decarbonization is widely recognized.

The study begins with a few facts showing the global recognition of nuclear’s positive effect on the reduction of emissions. This July, the European Union added nuclear energy to the green activities listed in its Taxonomy, which serves as a guidepost for the investors and companies in identifying which activities are sustainable and which are not.

Then, Ontario Power Generation, a Canadian utility company, issued green bonds that included nuclear energy in its use of proceeds. The bonds were oversubscribed sixfold.

The authors of the study also mentioned the words of Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency, saying at the Sharm el-Sheikh Conference of Parties in November 2022 that nuclear power was making a comeback.

However, having reviewed green and sustainable bond frameworks of 30 global systemically important banks, the authors have come to the conclusion that none explicitly includes nuclear energy in their sustainable finance taxonomies or they are ambiguous on whether it is included. “Despite nuclear energy’s potentially critical role in supporting deep decarbonization of the global economy, it is more commonly excluded from climate finance taxonomies, or the taxonomies are ambiguous on the issue. Thus, whether nuclear energy is considered green and sustainable or not varies widely across regions and institutions,” the study says. Out of the 30 global systemically important banks, 57% have explicitly excluded nuclear energy from their green or sustainable financing taxonomies, and 40% are silent on its inclusion or exclusion. The former group includes JP Morgan, Citi, HSBC, BNP Paribas, Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, and others. Those that are not explicit on the matter are Bank of America, Barclays, Mitsubishi UFJ, Agricultural Bank of China, Crédit Agricole, ING Bank, Morgan Stanley, Royal Bank of Canada, etc.

The researchers failed to find any pattern in the strategies of investment banks depending on the country’s region.

Germany and, paradoxically, France have excluded nuclear power from the permissible uses of proceeds from recent sovereign green bond issues, although the EU Taxonomy includes nuclear power. It is true, however, that the projects to be considered green according to the EU Taxonomy have to meet many conditions. For example, a new plant has to obtain a construction permit before 2045 and be located in a country that has plans to dispose of its radioactive waste by 2050. Life extension projects for the existing nuclear power plants can only be launched before 2040. On the other hand, Électricité de France has included nuclear power in its own green bond framework despite the fact that nuclear power is not considered ‘green’ at the national level in France and proceeds from sovereign bonds cannot be allocated to finance nuclear energy development.

The green finance framework of the UK Government also explicitly excludes nuclear power as of 2021, according to the study. And this is despite the fact that the UK national energy strategy provides for eight reactor units to be built by 2030. The reason is that many ‘sustainable’ investors recognize the criteria for excluding nuclear power.

In Asia, Indonesia and India (also surprisingly!) have excluded nuclear energy from their taxonomies. By contrast, China included nuclear in the list of industries the country’s regulators consider sustainable back in 2021. South Korea included nuclear energy in its K-Taxonomy in September 2022.

The deep pockets such as development banks, including the World Bank, exclude nuclear from their taxonomies. In addition, the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) signed by over 5,300 investment and asset managers representing more than USD 121 trillion in assets, are critical of the inclusion of nuclear energy in the EU Taxonomy. The International Capital Markets Association (ICMA), which defines the widely used green bond principles, did not include nuclear in its list of eligible green projects either.

The authors of the study estimate the sustainable investing assets under management reached USD 35 trillion at the end of 2021 and are expected to grow to USD 50 trillion by 2025. “Due to the tremendous growth and continued momentum projected for sustainable investment, nuclear energy would likely benefit from being able to access this pool of capital,” the researchers believe. To improve the investors’ stance on nuclear power, they suggest the groups developing climate taxonomies talk with utility companies about their role in decarbonizing the planet.

This proposal is encouraging but it runs into the fact that utilities are investors in some energy projects. An example is NuScale Power constructing an SMR. And its investors appear to have grown increasingly disillusioned over the past year as NuScale’s stock fell by nearly two thirds from USD 15.32 on August 24, 2022 to USD 5.97 on August 31, 2023.

Where to get the money?

The nuclear power industry is growing despite concerns from financial institutions. The key sources of finance appear to be public. The largest nuclear countries – Russia, China, France, and the United States– are investing in the development of their nuclear programs but the amount of funding varies. China, for example, announced back in 2021 that it would build 150 reactors in 15 years. According to preliminary estimates, this will require about USD 440 billion. The US plans are far more modest, with USD 6 billion to be invested in the next five years. Out of this amount, USD 1.1 billion has been provided to the Diablo Canyon Power Plant to finance its life extension program. France has earmarked even less money for the nuclear technology: around EUR 1.2 billion is allocated under the France 2030 national investment plan to support the development of innovative nuclear reactors and emergence of ‘new players’ in the market.

As for Russia, Rosatom has been investing over RUB 1 trillion annually, equivalent to around USD 14.6 billion at the Bank of Russia’s average exchange rate for 2022 (RUB 68.48 per USD), for the second consecutive year. Of course, this money is not used to only finance the construction of nuclear power plants – it is also spent on the nuclear industry and nuclear community in general.

The International Bank for Nuclear Infrastructure (IBNI) could potentially become a financial source for the global nuclear industry. The bank was initially supposed to bring together 50 countries interested in developing nuclear energy. “It is envisaged that IBNI will be established in early 2023, with Member States (a coalition of no fewer than 50 sovereign governments) initially contributing shareholder capital of US $50 billion (50% or US $25 billion of which will be paid-in and 50% or US $25 billion will represent callable capital),” says the IBNI Initial Report and Action Plan. According to the document, the shareholder capital could grow from its initial level to USD 300 billion over the next 30 years in the best case scenario, and the bank could become a catalyst for investments worth USD 26 trillion. The IBNI Implementation Organization, which was to be established in early 2022, was planned to be a vehicle for the bank’s initiatives.

However, after the world went through dramatic political changes, the idea of setting up IBNI first halted and then transformed drastically. The bank now has a club-like format. “We see the initial group that is going to lead the effort to stand up the bank as comprised of potentially seven countries: the United States, Canada, Great Britain, France, Japan, [South] Korea, and the UAE,” IBNI board member Elina Teplinsky said in an interview to Energy Intelligence. The sources and amount of shareholder capital have also changed, with USD 5 billion to be invested by the participating countries. As IBNI’s Strategic Advisory Group Chairman Daniel Dean said, the bank hopes to acquire another USD 25 billion from private investors. A joint declaration in support of the bank is expected to be signed at COP-28, which will be held in the UAE this December.

The problem with IBNI seems to be that the sources of public investments are not very clear. As can be seen from the figures above, the potential IBNI Member States have little money even for their national nuclear projects, while the United States national debt has reached USD 32 trillion. Thus, there is an obvious question: in which countries will IBNI finance projects? In the Member States? But if, as the study shows, large institutional investors drag their heels on investing in nuclear energy directly, why would they be interested in the idea of investing through a bank? If they invest in third countries, other problems will arise. In particular, the problem of distributing roles in technological partnerships will come to a head in certain projects. The conflict between the American Westinghouse and the South Korean KEPCO proves that this will be a painful issue for the potential founders of IBNI. Westinghouse does not consider the South Korean APR-1400 project to be license-free and seeks a ban on agreements to build such reactors in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Saudi Arabia.

Private or, more precisely, individual investments could essentially become a source of funding for the construction of a nuclear power plant (albeit, only of small capacity). A worldwide example of this is Bill Gates, who is developing an SMR project with a sodium-cooled fast reactor. As practice shows, though, it is not an easy task to build a viable nuclear power plant. It became known in August the company would not be able to apply to the regulator (NRC) for a construction license this month. The application deadline was pushed back to March 2024. In addition, production cost of the reactor could double from initial estimates. This is common for pilot projects but hardly pleasant for an investor.

The reality is that only governments are so far ready to finance the development of nuclear technology. Russia is one of the world’s largest investors in nuclear energy. Rosatom offers its partners both the tried and proven solutions and develops and tests new ones. Read more on this matter in our Reactor Technologies section.