Going Green

back to contentsSustainable finance for nuclear projects was one of the key topics at the Annual Nuclear Conference 2020 held by Swedish research institute Energiforsk. The conference brought together energy strategy experts from European countries, representatives of public organizations, the IAEA and nuclear station operators to discuss the role of nuclear power in the region. Speaking at the conference, Polina Lion, Rosatom Chief Sustainability Officer, told the audience how the Russian nuclear corporation dealt with the requirements and limitations imposed by financial organizations.

One of the problems discussed at the conference is a limited risk appetite that is a level of risk that a bank is prepared to accept in making investments into large-scale projects, including nuclear construction.

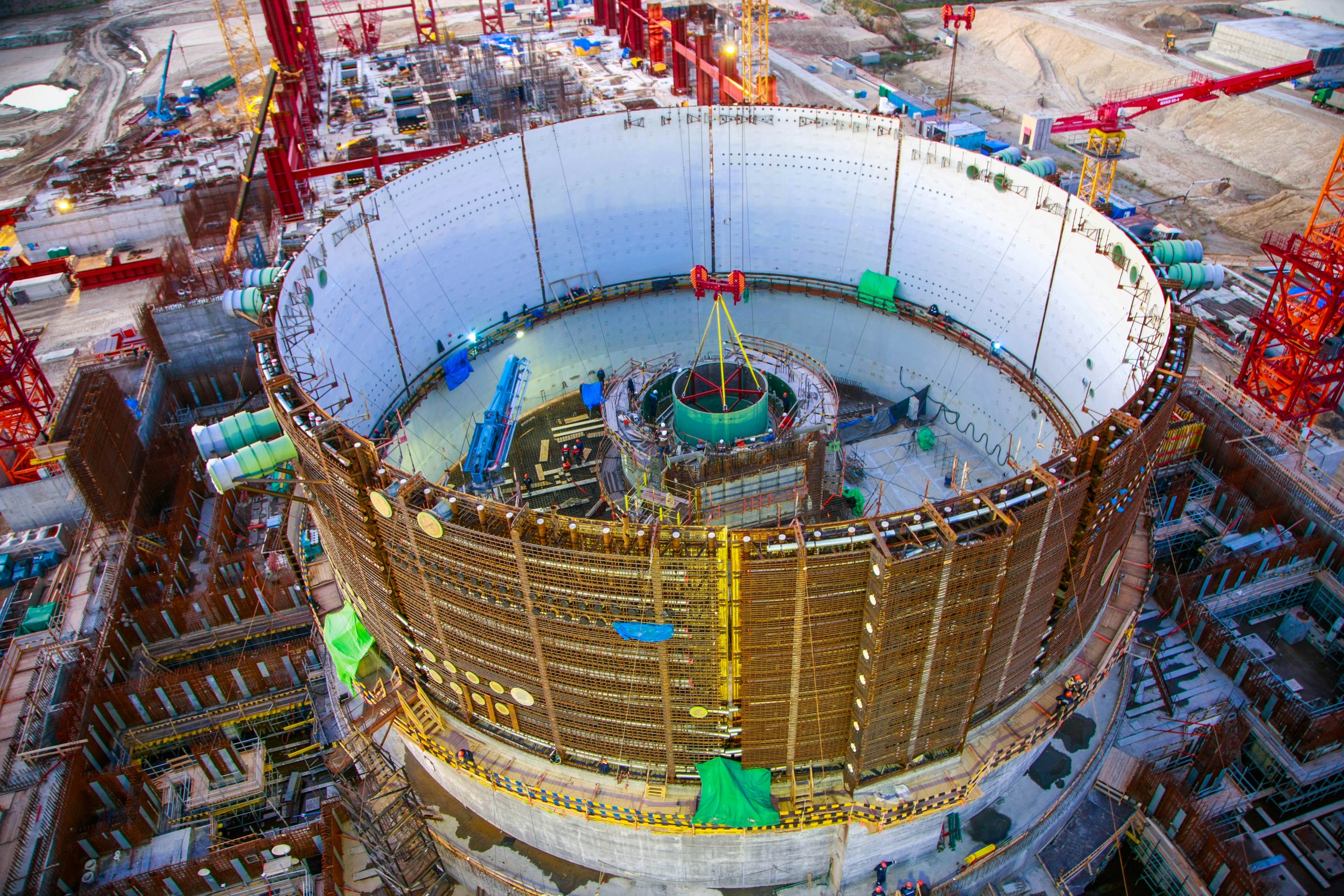

As international practice shows, commercial metrics alone do not make much sense for nuclear power plants. Every nuclear construction project costs many billions of dollars and is intended for more than half a century of reliable service. Taking into account construction, possible service life extension and decommissioning, the time horizon of the project can reach up to 100 years. The benefits of a nuclear project are not measured only in money earned from the power generation, but in economic development stimulated by reliable power supply, better education, science and technology, and improved quality of life. These benefits are hard to express in terms of measurable income.

Philosophy and practices of commercial banks are different: they usually expect a quick return on investment, so it is not a regular thing for them to provide multi-billion finance for technology-intensive projects with long payback periods.

A common ground does exist, though. Having respect for the position of commercial banks, Rosatom assumes that a complex nuclear construction project can be first distributed into several “building blocks”, such as electrical machinery, I&C systems, work done by local subcontractors, etc. Second, the financial model of such projects may involve export agencies, which support exports of value-added products, particularly high-tech products, and insure exporters against commercial risks. In Russia, it is the Russian Agency for Export Credit and Investment Insurance (EXIAR). Similar agencies exist in other countries, and they work with customers planning to build a nuclear power plant.

Nuclear seeks inclusion into development banks’ mandates

It seems logical that nuclear power plants as infrastructure projects contributing to the development of national economies and well-being of people should be financed by development banks, such as the World Bank and its regional divisions or the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank founded at the initiative of China. These banks finance construction of large ports, technically challenging bridges and highways that cost many billions of dollars and have long payback periods (or sometimes bring no return at all).

However, mandates of development banks (documents defining the scope of industries and projects they are willing to finance) often specify that nuclear power projects are not considered as investment targets. Things sometimes goes against logic, for example, earlier Rosatom Newsletter wrote that the African Development Bank was ready to finance biomass energy projects (carbon-intensive projects), but was unwilling to finance nuclear power plants.

One might wonder why this happens. It is safe to assume that people are afraid of nuclear power. It was repeatedly mentioned at the Energiforsk’s Conference that people were not informed about the advantages of atomic energy.

Public opinion surveys confirm this point of view. According to a poll conducted by France-based Orano Group last June, 69% of respondents are sure that nuclear power plants emit greenhouse gases. Even less is known about applications of nuclear energy or multi-level protection and safety systems.

Large power plants are far from being the only application of nuclear technology. Another good example are nuclear science and technology centers offered by Rosatom. They include a research reactor, different laboratories and multi-purpose irradiation facilities. For example, such facilities could be used to disinfect grain, fruit and vegetables. Since irradiated agricultural produce has a longer shelf life, this improves yield (seeds do not rot, have better storage life and higher germination) and supports exports (irradiated products meet safety requirements for imported foods). Research reactors could also be used to produce medical isotopes for diagnostics and cancer treatment. Construction and operation of a nuclear science and technology center helps train local staff and educate students in nuclear physics, material science and other fields of fundamental and applied physics. This knowledge and expertise will later contribute to the development of the national nuclear infrastructure and prepare the country for the potential construction of a nuclear power plant. Finally, a nuclear science and technology center helps raise public awareness of nuclear technology and give local researchers first-hand experience.

It turned out, though, that international development banks are not willing to finance any projects involving nuclear technology, not just nuclear power plants. Is this a game over? Or is it possible to convince banks otherwise?

It seems that a more detailed description of finance requirements for nuclear projects could be a solution to the problem. A positive example here is a new wording that, despite Germany’s nuclear power phase-out, was included into the mandate of Euler Hermes, one of the world’s largest export agencies specializing in export credit insurance. Now it reads, “In line with previous practice, Hermes Cover is not available for the delivery of goods and services for nuclear power stations. This basic exclusion does not apply to transactions whose purpose is to enhance the safety of existing facilities or are required for the shutdown, dismantling and disposal of nuclear power stations. Likewise, goods and services not related to commercial electricity production, e.g. research reactors and nuclear medicine equipment, are exempt from this exclusion.” It should be noted that Euler Hermes is wholly owned by German Allianz SE.

“Explaining benefits of nuclear technology and maintaining a dialog with development institutions will finally help make their mandates more specific,” Polina Lion stressed.

Europe defines criteria for green investments

There was much work done in the European Union over the last two years to establish uniform “sustainable” finance standards for different industries and projects. This work was necessary for financial institutions to have clear differentiation criteria for which industries and projects are “green” and “sustainable” and which are not. Banks and investment funds use the criteria to make their loan portfolios as sustainable as possible – this information is regularly disclosed in sustainability reports.

In December 2016, the European Commission established the EU High-Level Group (HLEG) on Sustainable Finance to help develop an overarching and comprehensive EU roadmap on the issue. On 31 January 2018, HLEG published its final report that presented the concept of sustainable finance and defined two imperatives for the EU’s financial policy framework. The first imperative is to improve the contribution of finance to sustainable and inclusive growth. The second is to strengthen financial stability by incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into investment decision-making. HLEG also made eight cross-cutting recommendations for the European financial industry to meet sustainability criteria.

In May 2018, the European Commission established the EU Technical Expert Group (TEG) on Sustainable Finance that had two tasks. The first was to establish the so-called EU sustainability taxonomy, that is a general framework for the development of an EU-wide classification system for environmentally sustainable economic activities. In June 2019, the TEG published a sustainable taxonomy report, which is being currently updated.

“The Commission will regularly update the technical screening criteria for the transition and enabling activities. By 31 December 2021, it should review the screening criteria and define criteria for when an activity has a significant negative impact on sustainability,” the European Commission said in December 2019.

The TEG’s second task was to develop the EU Green Bond Standard. The relevant technical report was also published in June 2019. The TEG proposed that the Commission created a voluntary, non-legislative EU Green Bond Standard “to enhance the effectiveness, transparency, comparability and credibility of the green bond market and to encourage the market participants to issue and invest in EU green bonds.”

By the end of 2019, the EU formulated the Green Deal concept. “The European Green Deal is our new growth strategy. It will help us cut emissions while creating jobs,” Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, said. The strategy sets out, “The European Green Deal is a response to these challenges. It is a new growth strategy that aims to transform the EU into a fair and prosperous society, with a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy where there are no net emissions of greenhouse gases in 2050 and where economic growth is decoupled from resource use.”

As part of the Green Deal, the European Commission expects to acquire at least EUR 1 trillion in sustainable investments over the next decade.

Some of this money is expected to flow in through the Just Transition Mechanism (JTM), a financing scheme for sustainability projects aimed at achieving carbon neutrality and other goals of the European Green Deal. Information about the JTM was published by the European Commission in January 2020. The JTM provides for the mutualization of risks carried by public and private investors, technical support and advice. The Just Transition Mechanism consists of three main sources of financing:

A new EUR 7.5 billion Just Transition Fund expected to generate at least EUR 30–50 billion of investments;

Invest EU ‘Just Transition’ scheme to mobilize EUR 45 billion of investments;

A new public sector loan facility with the EIB backed by the EU budget to mobilize EUR 25–30 billion of investments.

Every euro in the Just Transition Fund is expected to attract 1.5–3 euros from the European Social Fund and the European Regional Development Fund. Altogether, the JTM provides targeted support to help mobilize at least EUR 100 billion. The money will be used to finance employee retraining programs and projects aimed at improving access to clean, reliable and secure sources of electric power.

Reliable nuclear is in an unreliable position in Europe

Documents of the European Commission reflect a mixed attitude towards nuclear power. A perfect example is the sustainable taxonomy report published in June 2019. The section dealing with nuclear energy reads, “Evidence on the potential substantial contribution of nuclear energy to climate mitigation objectives was extensive and clear. The potential role of nuclear energy in low carbon energy supply is well documented.” The only challenge – the absence of a final solution to the nuclear waste problem – mentioned later in the report brings the TEG to an opposite conclusion, “Given these limitations, it was not possible for TEG, nor its members, to conclude that the nuclear energy value chain does not cause significant harm to other environmental objectives on the time scales in question. The TEG has not therefore recommended the inclusion of nuclear energy in the Taxonomy at this stage.”

In December 2019, debate sparked between the European Commission and the EU Parliament over whether gas and nuclear generation should be included into the list of sustainable sources of power. This will define which power plants are not considered sustainable in the European Union and should be discontinued. As a result, nuclear and natural gas remained on the sustainable list. “The EU Parliament and member states had sparred over the recognition of nuclear power, and of natural gas as a “transition” source of energy. France, Britain, and Eastern EU countries—the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Slovenia—rejected an earlier deal proposed last week that excluded nuclear power and natural gas,” Powermag.com commented on the December debates.

The wording of the report does not fully rehabilitate nuclear or gas, but it does not exclude them from the Green Deal or sustainable activities either, “The text does not preclude or blacklist any specific technologies or sectors from green activities, apart from solid fossil fuels, such as coal or lignite. Gas, and nuclear energy production are not explicitly excluded from the regulation, however. These activities can potentially be labeled as an enabling or transitional activity in full respect of the “do not significant harm” principle.” However, if the emission limits set for the energy industry (100 g CO2eq per kWh to be reduced to zero by 2050) are not changed, gas power generation will not fall within the scope of sustainable activities.

“The final decision as to the “color” of nuclear energy has not been made yet and, even if made, will be non-regulatory as is the entire Taxonomy. If it is finally concluded that nuclear meets sustainability criteria, this will be good. The industry will have access to cheaper commercial finance or at least will not be refused finance for not meeting the bank’s mandate. But even the status of a “transition” source of energy offers an opportunity to continue the dialog with financial institutions, which will be busy with developing their own internal rules and regulations for sustainable deals,” Polina Lion explained.

Participants of Energiforsk’s Conference realize this. The discussion at the Conference was centered on how the industry understands taxonomy metrics and how adequate they are for the nuclear power industry.

According to a representative of Europe’s trade association for the nuclear energy industry FORATOM, TEG members working on the sustainable taxonomy were divided into two sub-groups. Some of the experts were looking for advantages of each industry and its positive impact on the environment. They evaluated carbon dioxide emissions (carbon footprint over the entire project life in particular industries). They asked matter-of-fact questions and soon draw definitive conclusions. The other expert group, which was assessing negative impacts of the nuclear energy industry on the environment, could not long reach a consensus on specific countable metrics. It was difficult for TEG members, many of whom are not experts in the nuclear industry, to remain calm and unemotional.

As for now, the government is the only reliable source of finance for the nuclear power industry all over the world. With this in mind, governments and industry organizations interested in obtaining sustainable finance should work jointly on developing criteria that would fully reflect the contribution of nuclear energy to the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Nuclear contributes to the achievement of at least six of those, including access to clean energy, decent work and economic growth, innovations and infrastructure, sustainable consumption and production, global partnerships for sustainable development, and climate action. Considering these facts, it should be a no-brainer for the European regulators to put the nuclear industry on the sustainable list.