Goal: Self-sufficiency

back to contentsWe wanted to begin our regular talk about the nuclear market trends, the first in 2023, with a review of the Red Book, a biennial publication produced by the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency jointly with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and covering the global uranium market and resources. Although ready to come out, the publication was delayed. So, let us talk then about American and European attempts at making their nuclear fuel markets self-reliant.

Almost a year of waiting

For the anti-Russian sanctions imposed by the government of Canada, the Canadian uranium mining company Cameco could not receive its share of uranium produced at the Inkai mine in Kazakhstan almost until the end of the previous year (Cameco holds a 40 % stake in Inkai LLP, a joint venture with Kazatomprom). The company reported supply disruptions in its press release about Q1 2023 performance. Before the sanctions were imposed, yellow cake shipments to Canada used to be dispatched from Saint Petersburg.

It was as late as September when the first batch of yellow cake was shipped to Canada, but this time via the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, also known as the Middle Corridor, through Azerbaijan and Georgia. On December 20, Kazatomprom made an announcement, “The cargo comprising both uranium owned by Kazatomprom and uranium owned by JV Inkai LLP finally arrived at a Canadian port.”

Cameco’s press releases for the second and third quarters of 2022 warned that delays could affect equity earnings and dividend, as well as the share and timing of proceeds from Inkai.

In other words, actions of the Canadian government backfired on the company, which is also Canadian. While reporting Q3 2022 results, Kazatomprom pointed out, “There are currently no restrictions associated with the product shipments to our customers worldwide.”

Finnish uranium from tailings

Finland’s Terrafame announced plans to begin recovering uranium from tailings of its nickel and zinc production at the Sotkamo mine. “As the recovery begins, Terrafame will become a Finnish uranium producer, and thus will also play a role in building Europe’s energy self-sufficiency,” the company explains its move. Uranium recovery is assumed to begin no later than the summer of 2024 and reach full capacity of around 200 tons of uranium per year by 2026. To compare, Finland needs 421 tons of uranium annually after Olkiluoto 3 was put in operation, while all european nuclear stations together consume about 49,000 tons of uranium per year, according to WNA.

This is Terrafame’s second attempt at setting up uranium production. The first attempt was made back in 2011. In February 2011, the Sotkamo mine operator, Talvivaara Mining Company Plc, signed an agreement with Cameco to finance a uranium recovery plant with an annual capacity of 350 tons of uranium. Cameco planned its investments would pay off with uranium. The second agreement provided for the terms of shipments until the end of 2027.

According to the 2012 annual report, the Canadian company invested CAD 40 million in the project, which actually did not go smoothly. There were at least four leaks from the tailings pond (gypsum sediment pond) at Sotkamo in 2012–2013. The wastes contaminated nearby lakes, with the concentration of uranium in lower and medium water layers exceeding drinking water limits six times. The environmental impact sent shockwaves through the public and resulted in Talvivaara’s bankruptcy. Its founder and CEO Pekka Perä was fined half a million euros, and the project was closed. Cameco announced in its 2013 annual report that it had written off CAD 70 million of its investments in Talvivaara.

Terrafame became the successor of Talvivaara. In October 2017, the company filed for a uranium production license with the Finnish watchdog STUK and obtained it in February 2020. Re-launching uranium recovery operations requires EUR 20 million. After the plant reaches full capacity, the company plans to earn around EUR 25 million per annum.

What makes the recovery project really challenging is that uranium, which is present there in extremely low concentrations, needs to be separated from zinc and nickel inevitably remaining in the tailings. According to the Geological Survey of Finland, uranium content in Sotkamo’s black shales is 0.001 % to 0.004 %. To compare, Inkai ores contain 0.04 % of uranium, which is at least ten times higher.

Therefore, Terrafame’s business project is of local significance only. The recovery of uranium will account for “a few percent of Terrafame’s estimated net sales in the coming years,” the company says. It is quite likely that the new operations will change the structure of uranium supplies for the Finnish nuclear stations but they will hardly increase the uranium self-sufficiency of the European market. The company can call itself ‘Europe’s largest uranium producer’ for the only reason that there are no other uranium mining operations in the region.

Backing American uranium

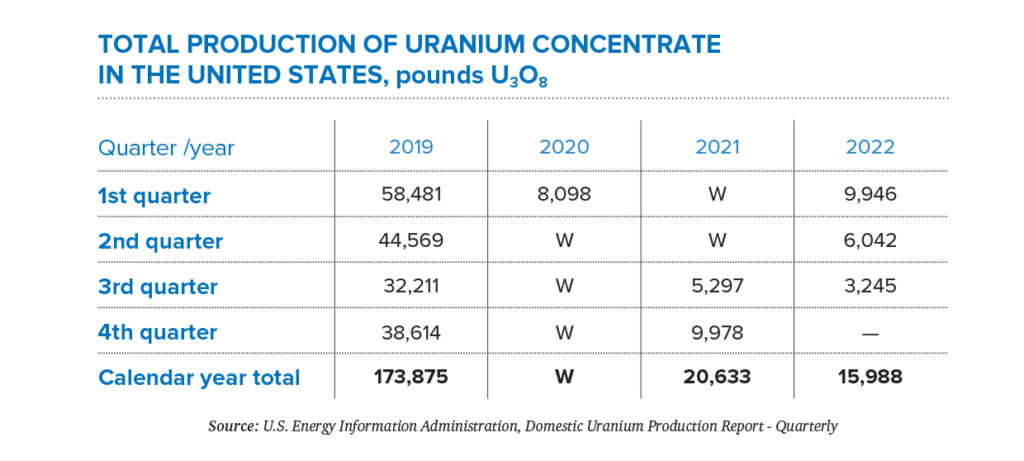

The US uranium mining industry has been in tatters for the last few years. “US uranium mines produced 21,000 pounds of triuranium octoxide (U3O8), or uranium concentrate in 2021. Production data was withheld in 2020 but 2021 production was down 88 % from 2019 production levels,” says the 2021 Domestic Uranium Production Report published by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA). For nine months of 2022, the United States produced 19,233 pounds of U3O8. It should be noted, though, that EIA accounted for only the first two quarters in its interim estimates (see the screenshot below), so the resulting amount is lower.

In the US, three mines were producing uranium in the first nine months of 2022. These are Nichols Ranch ISR Project (101 pounds), Ross CPP (367 pounds), and Smith Ranch-Highland Operation (2,777 pounds). It is evident that only the last of the three mines operates on a commercial scale.

In late June 2022, the National Nuclear Security Administration, a US Department of Energy agency, issued a solicitation to purchase up to one million pounds of U3O8 for the strategic reserve. The US Congress allocated USD 75 million for this purpose back in 2020.

Individual awards will range from 100,000 to 500,000 pounds of U3O8. It can be supplied by a vendor that has produced uranium at a domestic recovery facility at any time since January 1, 2009. Interestingly, the uranium to be procured must be from inventory already in storage at the Honeywell Metropolis Works uranium conversion facility in Illinois.

Based on the proposals received, five companies were selected, including Energy Fuels Inc., Strata Energy Inc. (a subsidiary of Peninsula Energy Limited), enCore Energy, Ur Energy, and Uranium Energy Corp. The purchase price ranged from little less than USD 60 to little more than USD 70 per pound. In 2021, the weighted average price was USD 33.91 per pound of U3O8, according to the 2021 Uranium Marketing Annual Report. In 2022, both the spot and long-term prices hovered around USD 50 per pound.

One million pounds of U3O8 is equivalent to about 385 tons of uranium. For reference, the US-based nuclear stations need 17,587 tons of uranium per year, as estimated by WNA. In 2021, according to the 2021 Uranium Marketing Annual Report, “owners and operators of U.S. civilian nuclear power reactors purchased a total of 46.7 million pounds U3O8e (equivalent) of deliveries from US suppliers and foreign suppliers during 2021.” Since 46.7 million pounds make nearly 17,963 tons of uranium, one million pounds that NNSA intends to procure can hardly be called a reserve because it covers a little more than 2 % of the US annual demand. Truly strategic reserves are made by consumers themselves. “Total US commercial inventories were 141.7 million pounds U3O8e at the end of 2021, up 8 % from 131 million pounds at the end of 2020,” says the 2021 Uranium Marketing Annual Report.

The government-funded procurement will give uranium companies a chance to earn some money, although it is not quite correct to call them ‘uranium.’ For example, Energy Fuel Inc. last sold uranium in 2019 for USD 66,000, while its primary source of income in 2019–2021 was ‘alternate feed materials processing and other.’ Its sales amounted to USD 3.18 million in 2021 and only USD 1.66 million in the COVID-affected 2020. The company survived by selling assets in 2021 to pay its debt. Its general and administrative expenses alone came in at about USD 14–15 million per annum in 2019–2021. The company hopes to cash in USD 18.5 million by selling uranium to the strategic reserve.

It is not difficult to compare the data and figure out the true position of the company. No more difficult is to understand that dependence on exports will persist. “The vast majority of uranium delivered in 2021 was of foreign-origin with Kazakhstan the top source at 35 % of total deliveries. Canadian-origin material accounted for the second-most material at 14.8 % of total and Australia third with 14.4 % of total deliveries,” says the 2021 Uranium Marketing Annual Report. In 2021, Russia was the fourth in that list with a 13.5 % share. Russian prices are the best for consumers as they are almost twice as low as those of the US producers and 1.5 times lower than the market average.

Looking for a new British fuel

The British government made it clear that it would establish a Nuclear Fuel Fund “to encourage investment in new and robust fuel production capabilities in the UK, to reduce reliance on civil nuclear and related goods from Russia.”

The mere reading of the press release and the Nuclear Fuel Fund Application Guidance shows there is nothing behind the declaration to ‘reduce reliance’ on Russian goods. Moreover, the Application Guidance directly says the opposite, that the nuclear reactors in the UK have everything they need to operate properly: “Nearly all the UK’s historic and existing nuclear reactors have been fueled using a UK-led supply chain for uranium enrichment and fuel fabrication. This has led to a domestic capability spanning nuclear fuel research and development (R&D) through to modern, well- invested commercial-scale enrichment and fabrication facilities, all of which are underpinned by a highly skilled workforce.”

The thing is the UK wants to build new reactors (24 GW of new capacity by 2050) and needs fuel for them. This is said clearly in the introduction to the Application Guidance: “However, whilst the domestic fleet has to date consisted of mostly a single reactor technology — Magnox and Advanced Gas-cooled Reactors (AGRs) are both gas-cooled reactors — the future UK fleet is expected to be made up of a variety of reactor technologies spanning other types of Gigawatt (GWe) reactors, Small Modular Reactors (SMR) and Advanced Modular Reactors (AMR), many of which require new and advanced fuel types. It is therefore likely that in future the UK supply chain will need to meet demand for a range of different fuel types.” Russia is not mentioned in the Application Guidance at all.

The Nuclear Fuel Fund will invest up to GBP 75 million, but GBP 13 million out of this amount has been invested to expand uranium conversion capacity at the Springfields nuclear fuel manufacturing site. GBP 50 million will be spent on new projects. The remaining GBP 12 million has not been earmarked yet.

The conclusion is rather straightforward: a fundamental property of the global natural uranium market is that uranium is produced and consumed in different regions. The geopolitical shift that shaped the world in 2022 caused concerns about the integrity of supply chains. In reality, only one such chain was broken and affected the fuel market. The Western media landscape propped by state declarations and corporate press releases is awash with ideas of self-sufficiency in nuclear fuel, but it is impossible in the USA or Europe either now or in the next five years at least.