Global Nuclear Fuel Supply in Early 2022

back to contentsCorporate annual reports are usually published in late March through the end of April. We planned to review the uranium market performance in 2021, but the global uncertainty made an article about nuclear fuel supply more relevant.

This text was written in the first half of April and does not take into account the latest developments.

Supply disruptions

Since the Russian special military operation in Ukraine began, the US, UK, EU and Japan have adopted several sanction packages affecting Russian business, particular businessmen and politicians.

The outcome was major supply disruptions, and each of them was caused by one or another ban on the part of the European Union, UK, US and Japan. And in each case, the result was growth of prices for energy, freight, transportation costs, etc.

The most affected was the EU because Russia is a high-profile player in each segment of the energy market. Russia accounts for 70% of coal (data by Brussels-based economic think tank Bruegel), 45% of gas and 34% of oil (both figures by IEA) in European energy imports. Russia also has a share in deliveries of wood pellets used increasingly often for home heating and thermal power plants.

No sanctions were imposed on nuclear fuel. Uranium was excluded from the energy import ban that was announced on March 8 and then imposed by US President Joe Biden. There were increasing calls, though, in the US and EU at the highest political level to ban imports from Russia. “Senator John Barrasso, Republican of Wyoming, introduced a bill in March to ban imports of Russian uranium, and a matching, bipartisan bill was introduced in the House last week,” The New York Times wrote on April 1. On April 7, the European Parliament adopted a resolution calling for an embargo on all energy imports from Russia, nuclear fuel included.

Production of nuclear fuel comprises several major stages, such as uranium mining, conversion, enrichment and fabrication. Russia’s positions in each of these segments are strong.

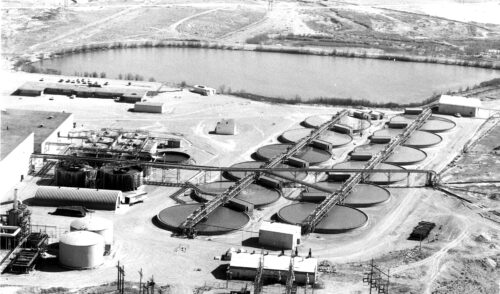

Mining

As of 2020 (no later data is available), Russia accounted for a relatively small share in the global output of uranium (6% or 2,846 tons). Another 9% (4,276 tons) is produced by Uranium One (part of Rosatom), which holds uranium mining licenses in Kazakhstan in partnership with the world’s largest producer Kazatomprom. From there, Rosatom companies account for about 15% of global output. This is not much, though. The USA is the country that worries the most about the security of uranium supplies since uranium from Russia makes about 20% of total demand from the US nuclear power plants.

US consumers have several options when it comes to buying uranium to replace imports from Russia. The first option is Canada, which is home to Cameco, one of the largest global producers of uranium. In February 2022, the company disclosed its plans to “transition McArthur River and Key Lake from care and maintenance to planned production of 15 million pounds per year (100% basis) by 2024, 40% below its annual licensed capacity, and to reduce production at Cigar Lake in 2024 to 13.5 million pounds per year (100% basis), 25% below its annual licensed capacity. This announcement was a major development in our business.”

In April 2022, the company published its 2021 annual report, disclosing plans for 2022 to produce up to 11 million lbs. of uranium, purchase 11 to 13 million lbs. and sell 23 to 25 million lbs. That means the share of Cameco will nearly double if compared to 2021 (6.1 million lbs.), but sales will remain flat – almost no change from 24.3 million lbs. in 2021. There is no other uranium mining company in Canada, except Cameco.

Australia is another major producer of uranium. According to WNA, Australia had three large operating mines in 2020 – Olympic Dam, Four Miles and Ranger. However, processing operations were halted at the Ranger mine in January 2021. Uranium mined at Olympic Dam is a by-product of copper, which is the main local product, so any increase in uranium production depends directly on the total output growth. Speaking about Olympic Dam’s performance for the six months ended December 31, 2021, CEO of BHP Mike Henry said, “All I can say is that any growth ambitions we have around Olympic Dam won’t happen unless the base business is running well… In the coming few years we’ll look at whether we can turn all of that into a high return growth opportunity for us in copper. Of course, it will be aided if we have the tailwinds of higher uranium prices but that’s probably it for now.” This does not sound like plans to increase production, does it? In 2020, BHP, an operator of the Olympic Dam mine, produced 3,611 tons of uranium, according to WNA. Its annual report for 2021 (ended June 30, 2021) says that the company obtained 3,267 tons of U3O8, which is 11% less than in the previous year (3,678 tons).

The third manufacturer is the Four Mile mine, which is currently owned by the US-based General Atomics. This company engages in nuclear technology projects and defense contracts. There is no publicly available information about the mine’s performance, except for WNA data on the output for the last six years. A sharp increase in the output took place after the sale in 2015. The output of U3O8 jumped from 1,183 tons in 2016 to 2,130 tons in 2020. Taking into account the specifics of its parent company and recent announcements by AUKUS regarding the construction of nuclear submarines and development of hypersonic missiles, we dare to assume that uranium mined at Four Mile is unlikely to be sold in the civil nuclear reactor market.

Production at the Honeymoon mine has not resumed after Uranium One first mothballed and then sold it to the Australia-based Boss Energy. Boss Energy also announced this February that it would join forces with First Quantum Minerals from Canada for precious metals prospecting.

The combination of those factors shows that Australia is unlikely to become a source of growing uranium supplies.

Kazatomprom, the world’s largest uranium producer, could theoretically increase global supply, but the company has not yet announced any changes in its production plans.

As a result of the recent frenzy around supply of uranium, its spot prices surged. According to UxC, the price was USD 59.5/lb. as at April 4 while in April 2021, the average spot price was as low as USD 28.9 per pound. The price growth was stimulated primarily by traders and financial institutions. Long-term prices also began to grow this March after remaining flat at about USD 43/lb. since September 2021 when they surged on the back of inflationary price growth in 2021.

Conversion

According to WNA, five uranium conversion plants (plants that transform the U3O8 yellowcake into the UF6 gaseous uranium hexafluoride) operate across the globe (see the table below).

World Nuclear Association Nuclear Fuel Report (2021 edition)

Notes to the table read, however, that Orano has not achieved full production capacity yet – the process is not expected to be finished before 2023. The same is true for ConverDyn, a partnership between General Atomics and Honeywell and the only conversion plant in the US. The plant was shut down in November 2017 amidst declining demand for nuclear fuel and underutilization of conversion capacity after the Fukushima disaster. In 2021, it was decided to resume production at the plant, which is scheduled for early 2023.

The table shows that it is only Rosatom’s conversion plant that operates almost at its full capacity. It is easy to calculate its share in the global market, making about 38%.

A quick look at the table gives an understanding that the share of Rosatom, even with domestic supplies excluded, cannot be replaced until 2023 at the earliest.

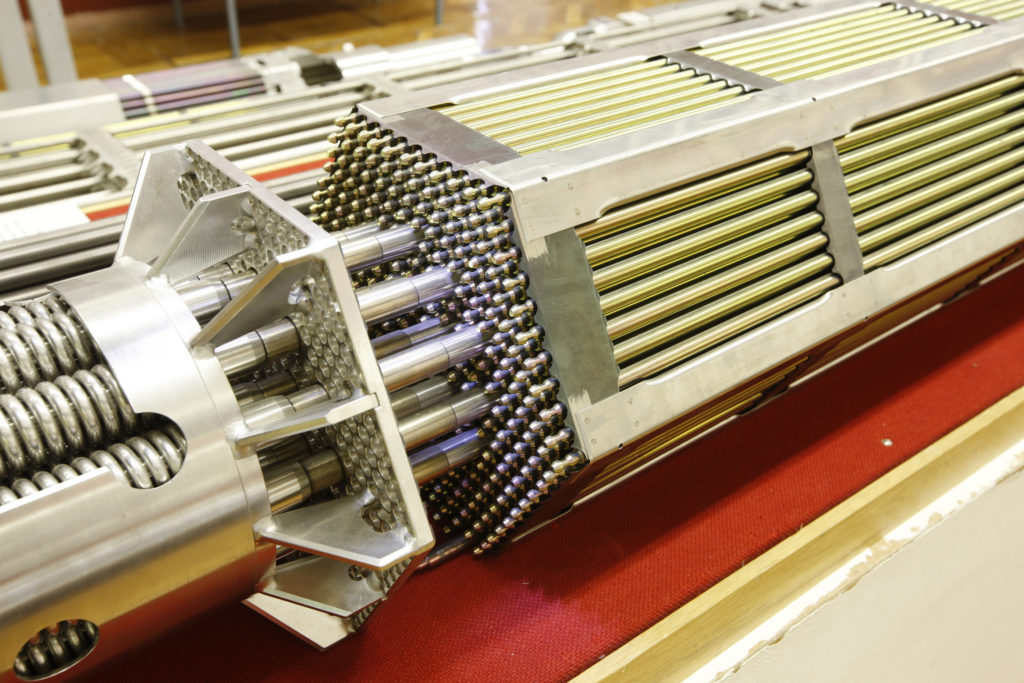

Enrichment

According to WNA, five companies in the world have the largest uranium enrichment capacity (see the table).

Source: WNA Nuclear Fuel Report 2019

It should be noted that Urenco plant in the USA accounts for 4,700 SWU of the company’s total annual capacity (almost 16,500 SWU). Rosatom holds a 36% share in the global enrichment market, and its capacity cannot be replaced for the time being. Enrichment facilities in France and China cater for their own needs in nuclear fuel. Urenco does not disclose its output directly. Its annual report for 2021 says only that the company “enriched enough uranium to generate an estimated 780,000 GWh of electricity from nuclear power.” Having converted this figure to SWU with an approximation formula proposed by WNA, we may assume that Urenco produced around 13,000 SWU, which makes about 70% of its design capacity. It is evident that the world does not have spare enrichment capacity to replace Russia.

But what if a new plant is built? “A significant number of refurbishment and optimization activities for our customers’ enrichment plants have been completed successfully; more are currently underway and upcoming in the future,” representatives of ETC, a manufacturer of gas centrifuges and a joint venture between Urenco and Orano, answered a question by Energy Intelligence. After that Phil Chaffее, an author of the article, makes a reasonable conclusion: “Refurbishment and optimization obviously doesn’t mean new centrifuges, and even if Orano and Urenco put in orders for more centrifuges tomorrow, it would take time for ETC to ramp up production to meet that demand.”

The fabrication segment is more diversified, and the largest nuclear fuel consumers, including the US and EU, meet their demand independently.

Conclusions

In the years to come, Russia will be an indispensable supplier across all the key segments of the nuclear fuel market. This is admitted by many experts and market players interviewed by different media and consulting companies. “There is not enough capacity in the western market to replace Russia,” Cameco’s Senior Vice-President and CFO Grant Isaac said in a talk with a representative of Scotiabank.

Nuclear power sector has been underinvested at least since 2011. The prospects of new investments are uncertain as market players are not confident in return on investments. Buying Rosatom fuel is just more cost-efficient and in some cases, it is critical for the profitability of nuclear power plants.

Any attempts to switch to another producer would mean that they will have to invest people, time and money at customers’ expense. One can only wonder how much the customer would have to pay for all those three resources at each of three production stages (mining, conversion and enrichment) to get high-quality nuclear fuel, which also needs to be approved by regulators. “We received a bid that was EUR 150 million higher (the estimated contract price was EUR 700 million – RN). Besides, they wanted us to cover all fuel development costs. The amount was too huge, so we opted for the Russian supplier. And fuel they make is really good,” Branislav Strýček, CEO of the largest Slovenian power company Slovenské elektrárne, said in an interview for Dennik.sk. According to him, migration to Westinghouse fuel will result in a decrease in performance by a few percentage points and a loss of “tens or even hundreds of millions of euros. We should realize that diversification will come at a cost.”

We can take an example of the gas market and gas-fired power plants to see how it happens. If compared with gas, nuclear fuel looks like a safe harbor, with prices rising much less dramatically than those for gas.

Taking into account economic aspects, a question arises: why start a hectic search for new suppliers? Is it for energy security and reliability of supplies? This reason might seem sound, but let us look back at the history to confirm or refute the argument. Statements might be arbitrary, but past events lay a foundation for justified conclusions.

Has Russia or the Soviet Union ever failed to deliver on its nuclear energy obligations? No, it hasn’t. There are no examples of such failures in history. By contrast, there is an example of how Russia fulfilled the 20-year HEU-LEU agreement, which came into force in 1993, the most difficult time of Russia’s contemporary history after the collapse of the Soviet Union. What is more, Rosatom continues to supply fresh nuclear fuel even with logistics disrupted after the sanctions were imposed in February 2022. In March, Slovakia received a shipment of the two-year fuel supply from Rosatom. In April, fuel arrived in Hungary. The Czech Republic has received three shipments from the end of February: “The Russian plane carrying nuclear fuel received a special permit for entry into the EU airspace, which was closed for Russian aircraft after February 24. This was the third and last flight with nuclear cargo. The Temelin NPP now has fuel for more than two years of operation, and Dukovany for three years,” ČEZ spokesperson Ladislav Kříž says.

In his book The New Map. Energy, Climate and the Clash of Nations, American historian of the petroleum industry Daniel Yergin admits that the United States argued repeatedly against energy imports, feeling uncomfortable with the idea of political rapprochement between Russia and Europe (see the quote below for details).

It is very much remarkable how close the current situation resembles what was happening 40 and 60 years ago. But what is happening now shows once again that energy imports from Russia continue and remain reliable.

Rosatom is a reliable partner who takes care of safety – safety of people, nuclear stations and customers.

Quote

“The debate about the political risks of importing energy from the Soviet Union and now Russia has been going on for a long time. The surge of Soviet oil exports to Europe in the late 1950s and early 1960s generated great alarm in the United States. Walter Levy, the preeminent oil analyst of the day, warned that the Soviets “regard oil as an instrument of national policy” and would “withhold it where it serves their political purpose.”… Washington adamantly opposed what was called the “Soviet oil offensive.” For the Europeans, it was more a matter of business… In the early 1980s, in the first years of the Reagan administration, dissension between the United States and Europe again erupted over Soviet energy exports—this time not about oil, but about natural gas… The Reagan administration, which was stepping up defense spending, did not want the Soviets earning money that would fund their own military buildup. Washington also feared that dependence on Russian gas, especially in Germany, could help Moscow generate fissures in NATO and provide a major pressure point if East-West tensions worsened. This was the time “to dig in our heels,” President Reagan said, and “just lean on the Soviets until they go broke.”