Russian Approach to Lithium

back to contentsFaced with a decrease in car deliveries and even the exodus of car manufacturers on the back of sanctions, Russia has embarked on further development of its domestic automobile industry. The focus is placed on electric vehicles as they have fewer parts and are easier to produce. Their key component is a battery made from nickel, cobalt, manganese, copper, aluminum, and, of course, lithium — metals that are now called ‘battery metals.’ Russia is fully self-sufficient in nickel, cobalt, copper, and aluminum; manganese is imported from several sources, and only lithium is yet a major concern. You will learn from this article how Russia deals with it.

Lithium is not mined in Russia, so self-sufficiency in this metal is a problem, dealing with which is high on the agenda.

Global picture

High demand for lithium is a global trend driven by the rapid development of electric vehicles, primarily in China. Supply cannot yet catch up with demand. What is more, the recent pandemic and anti-Russian sanctions have raised concerns about the integrity of the existing supply chains. As a consequence, lithium prices skyrocketed in 2022. In mid-November 2022, the price of lithium hit an all-time high of USD 84,500 per metric ton. By comparison, the price averaged USD 25,000 in 2018 and fell below USD 6,000 per ton of lithium in 2020. The price of spodumene (a lithium-containing mineral processed into lithium hydroxide and lithium carbonate) rose from USD 598 per ton in 2021 to USD 2,730 in 2022. In mid-September 2022, the price exceeded USD 7,800 per ton.

So, it can be safely said that the prices for lithium products have increased manifold during 2022 compared to the previous two years.

It is difficult to say how much demand has increased as the figures for the output of electric vehicles vary widely. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), 6.6 million electric vehicles were sold worldwide in 2021, twice as many as the year before. According to Ev-volumes.com, 4.3 million electric and hybrid vehicles were produced in the first half of 2022, an increase of 62 % over the same period in 2021. Morgan Stanley announced in late 2022 that the production of electric vehicles in 2022 was up 70 %, or about 2 million cars. That means around 2.86 million electric cars were produced in 2021, according to the estimates of the American financial company. We can assume that the variations in the figures are due to the classification of electric vehicles. For example, Morgan Stanley took only electric cars into account while the IEA also included hybrids in its statistics.

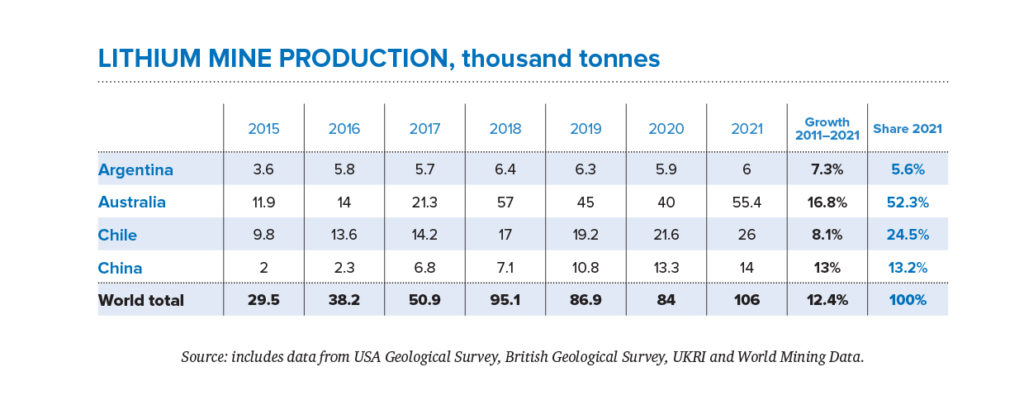

Anyway, supply was growing in response to demand. “The lithium market did not show any meaningful growth in 2019, with about 300,000 tons of the metal produced. Previously, the output had been rising by around 30–50 thousand tons per year. Now the market is growing at 200,000 tons a year,” Eric Norris, President of Lithium Global Business Unit at the American chemical company Albemarle Corp. told the Financial Times late last December.

As estimated by the Australian Government in a quarterly report released in December 2022, the global output of lithium (in terms of lithium carbonate equivalent) amounted to 691 thousand tons in 2022. The forecast for 2023 is 915,000 tons and 1.087 million tons for 2024. Demand is estimated at 745,000 tons in 2022, rising to 924,000 tons in 2023 and 1.091 million tons in 2024.

Thus, the Australian Government believes the shortage will not ease in the next two years, and that the price will continue to climb up. According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, the shortage of supply in the global lithium market reaches 80,000 tons in 2022, with the production totaling about 635,000 tons. The shortage will persist in 2023, BMI analysts say, but will sharply decrease to 5,000 tons. The decrease will be driven by growing deliveries in 2023 — they are expected to reach 863,000 tons, up 36 % year-on-year.

However, according to Stella Li, Executive Vice President of BYD, one of China’s electric vehicle manufacturers, the market will turn to surplus in 2023 because new lithium mines will be launched and prices will stabilize. S&P Global Market Intelligence has produced similar estimates. The company forecasts that the supply of lithium-containing products (in terms of lithium carbonate equivalent) will reach 858,000 tons in 2023, or 2,000 tons above demand.

The estimates compared, the market has no consensus on production volumes in 2022 and no single vision of prices, demand and supply in 2023. Significant market growth is the only thing everyone is united over.

In January 2023, the price of lithium fell to little above USD 70,000 per ton. There are two drivers behind the price movement. First, China abolished subsidies on new electric vehicles, and demand declined despite other demand-stimulating measures, such as tax incentives. The second driver is a sharp increase in lithium supplies in the market this year. Bloomberg estimates the increase could be 22 % to 42 % as compared to the previous year. However, there was no unanimity in January in assessing the lithium market changes either.

Australia is currently the biggest producer of lithium. According to Visualcapitalist.com, its market share is 52 %. Chile is the second largest producer, accounting for a quarter of the global supply, followed by China (13 %) and Argentina (6 %). Four other countries (Brazil, Zimbabwe, Portugal, and the United States) produce 1 % of the world’s lithium supply each. The rest of the world accounts for as little as 0.1 %.

Lithium in Russia

The Russian Government estimates the country’s needs at about 3,000 tons — this is how much of various metal compounds was imported in 2021. It should be noted, though, that some of the imports are then exported in the form of other compounds. Russia’s internal demand for lithium is 400 to 700 metric tons. Lithium is used in the nuclear power industry, in energy storage systems, and in the production of slag-forming mixtures for ladles and lubricants for mining operations.

There are plans to set up domestic production. “Accelerated development of lithium ore mining projects at the Zavitinskoye, Polmostundrovskoye, Kovyktinskoye, Yaraktinskoye and Kolmozerskoye deposits in 2023–2030 will help meet most of domestic demand for lithium,” says the Russian Metals Industry Development Strategy 2030 adopted last December.

All of the mentioned sites are not easy to mine. For example, Zavitinskoye is an already depleted deposit. Lithium was mined here from 1941 until 1997. The current plan is to extract lithium from the production waste, and Krasnoyarsk Chemical and Metallurgical Plant is obtaining a license for this purpose.

Kovyktinskoye is the largest gas field in Eastern Russia. Lithium is contained in the associated brines, and there has been talk about its extraction for several years. The process accelerated in 2022, and Kovyktinskoye was put into production in late December 2022.

Rosatom also plans to extract lithium — but from ores, not brines. This is a common practice adopted, for example, at Australian pegmatite deposits containing mostly spodumene.

In Russia, a pegmatite deposit, Kolmozerskoye, is located in the Murmansk Region. It is believed to be the most promising deposit, and Rosatom plans to develop it in partnership with the Russian mining major Nornickel. “Nornickel’s products have long played an important role in manufacturing energy storage systems. By expanding our range of metals with lithium, an essential and much sought-after raw material, we intend to strengthen our position as a key supplier for the battery segment,” Nornickel’s press release about an agreement with Rosatom signed in April 2022 quotes its President Vladimir Potanin.

No mining license for Kolmozerskoye has been issued yet. According to the official data as at July 1, 2022, P1 category resources (inferred resources with the greatest probability) at Kolmozerskoye amount to 13.5 million tons of ore containing 152,600 tons of lithium oxide, 1,215 tons of tantalum pentoxide, and 1,485 tons of niobium pentoxide.

On February 8, 2023, in accordance with the decision of the auction commission, the subsoil use rights for the Kolmozerskoye deposit were transferred to Polar Lithium LLC, a joint venture of Atomredmetzoloto and Norilsk Nickel. As expected by Rosatom and Nornickel, the output of lithium hydroxides and/or carbonates at Kolmozerskoye may amount up to 45,000 tons per year in terms of lithium carbonate equivalent.

Thus, within a few years, Russia may have a large mining project that will fully — and even abundantly — meet its current domestic demand for lithium.

According to Rockwood Lithium, one of the world’s key lithium producers, a 25 kWh car battery needs 44 pounds (almost 20 kg) of lithium carbonate. It can be roughly calculated that a 4 GWh battery plant will require about 3,200 tons of lithium carbonate. This means that the annual capacity of the Kolmozerskoye deposit should be sufficient to supply four such plants, and there will be more lithium left for sales to other consumers.

Kolmozerskoye deposit: facts and figures

Source: Solid Mineral Resources of the Russian Arctic (collective work published by Fedorovsky Russian Research Institute of Mineral Resources)

The Kolmozerskoye deposit has 70 pegmatite veins, 11 of which are of commercial value. Pegmatite bodies are covered by a thin (a few meters) layer of moraine sediments from above. The ore bodies have a plate-like shape; large veins are 570 to 1,680 m long and 10 to 50 m thick. The veins are grouped into parallel vein zones, the largest of which comprise two commercial blocks, Big Potchevarak and Small Potchevarak. Li2O content varies from 0.8 to 1.3 %, averaging 1.14 %. The deposit is expected to be mined as an open pit. A flotation and gravity separation method has been developed for Kolmozerskoye lithium ores.