Return of Fatfleshed Kine

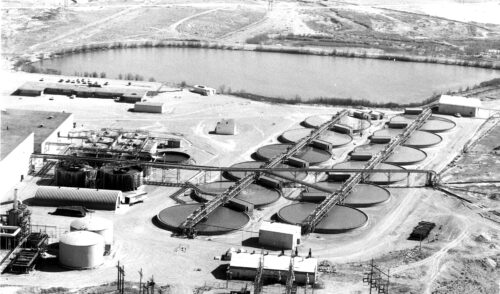

back to contentsFor over a year, spot and contract uranium prices have remained above USD 40 per pound, in a first since May 2013 and June 2016, respectively. According to reports, most of the mining companies have increased their revenue and net profit. Meanwhile, the changing attitude towards nuclear on the back of the energy crisis provides ground for a yet cautious optimism for demand growth as preparations are made to put mothballed and new mines in operation.

The past six years of low contract prices straddled post-Fukushima pushback from investors, mine closures, and asset sell-offs. Those years can be compared with the biblical leanfleshed kine from the Pharaoh’s dream. The ‘leanfleshed’ years were followed by a coronavirus pandemic, supply disruptions, a vigorous growth of demand for metals during the post-pandemic recovery and, finally, a conflict in Ukraine, economic struggles and a global energy crisis. It was those unprecedented events that raised concerns over stability of supply and whet investors’ appetite, having pushed the price of U3O8 upwards.

The first price hike happened in 2020 on the back of the pandemic. Then the price moved further up in the autumn of 2021 as the global economy began to recover and commodity prices rose. The third hike occurred this March when the average monthly spot price spiked up to USD 58.2 per pound while the maximum weekly price in March stood at USD 63.75 per pound. Long-term prices followed. In June and July, the average contract price reached USD 51.5 per pound. Uranium mining companies made the best of the situation as their financial performance improved significantly.

Cameco

Canadian Cameco’s uranium output soared more than 3.6 times in the first half of 2022, having increased from 1.3 to 4.7 million pounds. Its revenue from uranium sales, transportation and storage posted, however, a more moderate growth over the same period, up 67 % from USD 461 mln to USD 770 mln. In return, gross losses of USD 89 mln turned into profit of USD 78 mln. Year to date, the Canadian company have signed supply contract for over 45 million pounds of uranium and ‘have a significant and growing pipeline of contract discussions underway.’ According to the company, customers are becoming more interested in long-term contracts.

Cameco produces a little more than a third of uranium it sells. To some extent, this state of affairs is explained by the fact that the company has not been consolidating the results of Kazakhstan’s Inkai uranium mine since 2018, so Inkai uranium is accounted for as purchased material. “Based on an adjustment to the production purchase entitlement under the 2016 JV Inkai restructuring agreement, we are entitled to purchase 4.2 million pounds, or 50 % of JV Inkai’s updated planned 2022 production of 8.3 million pounds… Due to equity accounting, our share of production is shown as a purchase at a discount to the spot price and included in inventory at this value at the time of delivery,” the company’s report says. Generally, though, growing prices drive not only Cameco’s earnings but expenses, too: “For the remainder of 2022, the volume of purchase commitments sensitive to the spot price is higher than the volume of committed deliveries that are sensitive to the spot price. As a result, our cash flow is expected to move in the opposite direction from the uranium spot price as cash flow is expected to be more sensitive to price changes than adjusted net earnings.”

Kazatomprom

“The company demonstrated very strong financial performance in the first half of 2022, capturing a sharp market upturn over the last 12 months,” says Yerzhan Mukanov, acting Chairman of the Management Board and Chief Operations Officer at Kazatomprom (Kazakhstan).

Its revenue for the first six months of 2022 amounted to KZT 493.7 bln, or over USD 941 mln (Kazakhstani tenge is hereinafter converted to US dollar at the average 1H 2022 exchange rate of KZT 524.46 per USD), more than two times as much as in the previous year. Operating profit was up 188 % to reach KZT 167.4 bln (more than USD 319 mln). Net profit increased from KZT 184 bln to KZT 467 bln (from USD 350.8 mln to USD 890.4 mln), up 2.5 times. “Those impressive results were triggered by the market improvement and higher sales resulting from a growing number of delivery orders for the first half of the current year,” the company’s statements say.

Production in the first half of 2022 was somewhat lower year-on-year, whether in Kazakhstan (little more than 10,000 t vs. 10,450 t in 1H 2021) or at Kazatomprom (5,410 t vs. 5,860 t, respectively). By contrast, sales grew 46 %, from nearly 5,180 t to 8,000 t at Kazatomprom and from almost 6,200 t to 9,000 t in Kazakhstan. Another telling fact is that Kazatomprom, like Cameco, also mentions customers’ interest towards long-term contracts.

Orano

The mining division of the French company posted a 12.7 % growth in revenue, from EUR 662 mln to EUR 746 mln. According to Orano, the growth was mostly driven by ‘favorable effects of the increase in uranium prices’ and also by a positive conversion effect between the US dollar and the EUR. However, the growth could have been much higher if not for the backlog sales (shipments made but not yet paid for).

Operating income for the mining division remained almost flat, having increased from EUR 183 mln in the first half of 2021 to EUR 186 mln in 1H 2022. The figure experienced a mixed effect from a number of factors: “Positive price/exchange rate effects over the half-year in connection with the increase in uranium and dollar prices, as well as the absence of COVID impact on activities in 2022 after the production shutdowns in Canada between January and the beginning May 2021 offset a less favorable production mix over the period and the increase in the cost of materials.” The company does not disclose its six-month production figures.

BHP Billiton

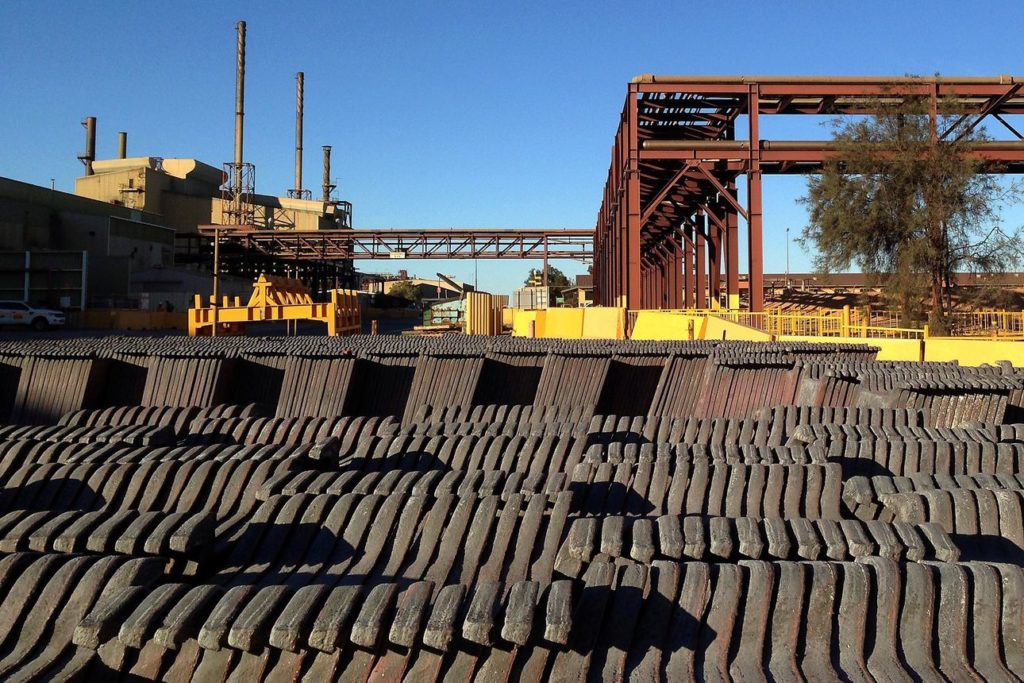

BHP Billiton (Australia) is, perhaps, the only major mining company that reported a decline in financials in the uranium segment. “For FY2022, BHP’s green revenue from uranium was US$207 million, which is a decrease of 17 per cent on FY2021,” the company wrote in its report for the 2022 financial year ending June 30. BHP Billiton does not make any comments on the reduction of revenue but it might be attributed to a decrease in the output. With 3,267 t of uranium produced in the 2021 financial year, the company’s output in 2022 amounted to as little as 2,375 t, down 27 % y-o-y. Sales also went down from 3,816 t of uranium in 2021 to 2,344 t in 2022. The main driver behind the decline of uranium output was a decrease in the production of copper, the key product of BHP Billiton’s Olympic Dam mine due to a ‘major smelter maintenance campaign (SCM21), which included COVID‑19 impacts on the availability of workforce.’ The maintenance campaign was finished this January.

Rosatom

Rosatom’s mining division supplies yellow cake to its nuclear fuel division for subsequent processing, so those supplies affect the prices only insofar as they are not sourced in the market and do not increase demand. The Russian nuclear corporation neither discloses production data of its mining subsidiary Uranium One operating in Kazakhstan nor makes any comments on its performance in an effort to avoid speculations.

Production complexities

Despite the profits the companies make in the current situation, production and financial difficulties keep eating away at the financial buffer they have just managed to set up. This is highlighted not only by Orano in its comments on low operating profits, but by other uranium producers as well. “We need to factor in the growing inflation pressure and potential delays in the production supply chain as such delays may affect our production plans,” Kazatomprom writes. COVID-related supply disruptions have already caused the company to fall behind its production schedule, but Kazatomprom hopes to catch up with it by the year-end.

Cameco faces production issues, too. “At the Key Lake mill, we have encountered some challenges with respect to the availability of critical materials, equipment and skills for some of our critical automation, digitization and other projects. In addition, after four years on care and maintenance, we have experienced some normal commissioning issues as we work to safely and systematically integrate the existing and new assets with updated operating systems at the mill.” Experiencing problems with the commissioning, Cameco does not expect production to resume before December.

Cautious rise

News is coming in that can be interpreted — despite the existing difficulties — as cautious production expansion. For instance, Kazatomprom announced that it would cut its 2024 production target by 10 %. But given that the output has been since 2018 — and will remain through 2023–20 % below the production target, a 10 % cut is actually growth. It should be taken into account that the output commitments provided for by the production license also grow, so Kazakhstan will increase uranium production from 21–22 thousand tons in 2022 to 25–25.5 thousand tons in 2024.

Cameco also announced it would resume operations at its mothballed McArthur River and Key Lake mines. However, after the production is resumed, the two mines — as well as its flagship Cigar Lake mine — will operate at two thirds of their aggregate capacity: “Starting in 2024, it is our plan to produce 15 million pounds per year (100 % basis) at McArthur River/Key Lake, 40 % below the annual licensed capacity of the operation. At that time, we plan to reduce production at Cigar Lake to 13.5 million pounds per year (100 % basis), 25 % below its annual licensed capacity, for a combined reduction of 33 % of licensed capacity at the two operations.”

Orano announced it had signed an addendum to the current subsoil use contract enabling KATCO, a joint venture between Orano and Kazatomprom, to mine uranium at the South Tortkuduk parcel of the Muyunkum uranium deposit for about 15 years. The parcel reserves are estimated at about 46,000 metric tons of uranium. Interestingly, KATCO will not operate at its full capacity until 2026 either. “Given the work required to bring this new parcel on stream, the KATCO JV’s total production could be limited to approximately 65 % of its nominal capacity (about 2,600 tons of uranium per year) for the next two years, with an estimated return to its full production level of about 4,000 tons of uranium per year in 2026 at the earliest,” the company’s press release says.

Rosatom also increases its mineral resources. In Namibia, Russian geologists discovered a uranium deposit suitable for in-situ leaching, the most cost-efficient and environmentally friendly method of uranium extraction. No such deposits have ever been found in Namibia before. Rössing (almost exhausted) and Husab (both owned by China General Nuclear Power Group) are open pit mines. At present, exploration activities continue on the flanks of the newly discovered deposit and preparations are underway to begin pilot production of uranium.

Conclusions

As the current market situation suggests, uranium producers had an opportunity to create a financial cushion during the first six months of the year — this process started about a year ago. As the number and size of long-term contracts are growing, the future is getting more secure. “Our pipeline of existing contracts ensures a sufficient level of confidence that additional production volumes in 2024 will be absorbed by market demand,” says Kazatomprom’s press release.

However, major uranium producers are far from going euphoric. “In our opinion, the fundamental shift in the supply-demand balance is still going on, mostly due to false assumptions that secondary sources of supply are unlimited. This creates new opportunities for Kazatomprom as a reliable supplier,” the Kazakhstan company wrote in its report.

Generally, the uranium market is affected by mixed trends. On the one hand, it is evident that concerns over the security of supplies raise interest in uranium and, consequently, push prices up, making buyers lean to long-term contracts. On the other, it is clear the drivers of this interest are not yet seen as fundamental. It should be also noted that the spot prices have not risen above the USD 50 per pound mark since mid-July.

While last year’s autumn and winter were defined by an economic upturn, price hikes and a shortage of everything, energy commodities included, this spring and summer faced disruptions in trade, production and supply chains, but the acute crisis resolved itself in a growth of revenue.

Interest towards nuclear energy is on the rise but it has not yet turned into an all-encompassing trend. In this context, Rosatom is a driver of nuclear energy development in Africa and mainland Europe. The Russian nuclear corporation has obtained construction licenses for new reactors in Egypt and Hungary, with first concrete to be poured in the latter in 2023. Keep in mind that previously first concrete was poured in Europe in 2007 (at Flamanville 3) and in Africa in 1976 (at Koeberg 2).

Politicians, economists and analysts keep saying that the future is vague and born right now, so it is not unlikely that uncertainty will be our new reality for long. No wonder that, amidst uncertainty, Cameco makes an almost philosophical remark in the management’s discussion and analysis of its six-month performance: “Managing geopolitical uncertainty is not new for us. We have a long history of working with global business partners and international governments in the nuclear industry. We have learned the importance of taking time to evaluate evolving situations to understand the long-term implications of our decisions. Our values have guided us through past geopolitical uncertainties and will continue to do so during these uncertain times. If we find a misalignment, we will take appropriate measures to manage the risk.”