Uranium Prices Climb Higher

back to contentsAs uranium is becoming increasingly scarce, supplies will not grow in the short term. In September, natural uranium prices increased sharply reacting to that very revelation. Let us take a look at what this may bring about.

Longtime shortage

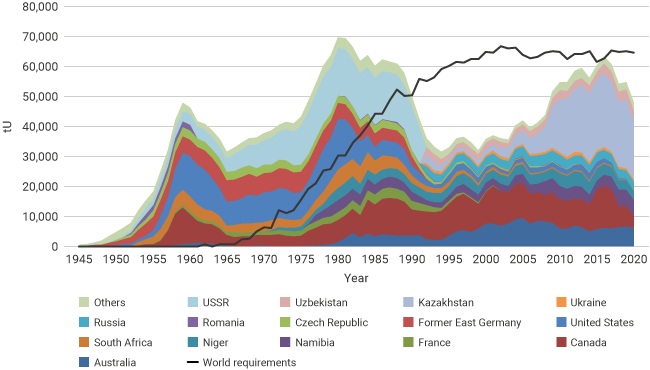

The uranium produced worldwide has been insufficient to meet the global reactor requirements for over 30 years. The primary cause of the decrease in production was the collapse of the Soviet Union, which used to be the world’s largest uranium producer since around 1965. In the 2010s, production and consumption converged. According to the WNA (see Fig. 1), supplies from natural sources met 85% to 98% of uranium needs in 2013–2018, with the highest percentage reached in 2015. That year, as the prices of industrial metals were falling, the uranium price, although low, remained relatively stable, hovering around the range of about USD 34–37 per pound of U3O8 (USD 36.6/lb on the annual average). Apparently, on the back of shrinking demand after the Fukushima accident, the producers in Kazakhstan and Canada sought to maintain revenues by increasing supply. Then the tactics changed, and some producers cut production. The uranium output fell most drastically in Canada, from 13,100 tonnes in 2017 to 7,000 tonnes in 2018. In Kazakhstan, production fell from about 24,700 tonnes of uranium in 2016 to below 19,500 tonnes in 2020.

To be fair, the production was affected not just by the market factors, but also by the obligations to the government (production cuts in Kazakhstan were determined by the provisions of subsoil use contracts), mine depletion (COMINAK deposits in Niger and the Ranger Mine in Australia), willingness or necessity to increase output (Husab in Namibia and Four Mile in Australia), and others.

In 2021, uranium production and prices started to rise again amidst the post-COVID global recovery and, especially, growing prices for key commodities. In September 2021, the price passed the USD 40/lb mark and has never fallen below since. Global production also increased with a slight lag (47,730 tonnes in 2020, 47,800 tonnes in 2021 and 49,360 tonnes in 2022). March 2022 saw a surge in uranium prices on the back of concerns over sanctions against Russia although it quickly became clear that the situation was difficult but workable. Canada’s Cameco reported logistics problems in the same year as the national rules prevented it from exporting uranium from Russian ports. The company started exporting uranium from Kazakhstan, where it co-owns and operates the Inkai mine, via the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route. However, delays were lengthy: the uranium that was supposed to arrive in Canada in the first half of 2022 did not reach the country until December.

For about a year – from April 2022 to April 2023 – uranium prices were quite stable, fluctuating in the range of USD 47–53/lb. Reporting its operating results for 1H 2023, Kazakhstan’s Kazatomprom noted the spot market had been fairly quiet for most of April but the market activity picked up in the last week of the month, with the spot price rising to USD 53.8/lb U3O8. In May, expectations of increased demand from the financial sector drove the price up to USD 54.50/lb. In June, sustained demand made the spot price climb further up to USD 57.5/lb mid-month, but it then retreated to USD 56/lb by the end of the month. “According to third-party sources, the spot market saw a significant decrease in activity year over year in the first half of 2023,” the operating report says. In the second quarter of 2023, the plans were voiced and decisions made to refuse the supply of Russian nuclear fuel products, which worsened the market separation. In April, five countries agreed to join their efforts for reducing dependence on Russian nuclear fuel, and the US Congress was drafting bipartisan bills to ban imports of Russian uranium and introduce a domestic nuclear fuel program. Urenco approved investments to increase enrichment capacity at its US-based facility. The combination of the relatively low market activity and the reference made in Kazatomprom’s report to the expectations of increased demand suggest that fear was one of the most essential factors driving the price increase in the second quarter.

This fear and the desire to be on the safe side by protecting supplies from the surprises of spot trading caused changes in the market structure. While about 12,500 tonnes of uranium was sold in the spot market and around 27,500 tonnes in the long-term market in the first half of 2022, the sales in the same period of 2023 were as little as 7,000 tonnes of uranium in the spot market and as much as 41,600 tonnes in the long-term market. Thus, the share of spot sales decreased from 31.25% to 14.4%, while the total market size increased by 8,600 tonnes or 21.5%.

What’s going on now

The uranium prices stabilized in July, but the coup d’état that occurred in Niger late that month raised fears about the possible interruption of supplies. And they did interrupt because Benin, through whose port yellow cake from the landlocked Niger is shipped, closed the border. The border closure had another consequence, namely the inability to continue uranium production due to lack of necessary chemicals. “Given the ongoing closure of Niger’s main supply corridor and diminishing stocks of chemical products, SOMAÏR, the only mining company currently with mining operations in progress, has implemented a gradual reorganization of work by bringing forward its maintenance activities,” the French Orano, a co-owner and operator of the mine, said on September 13.

The impact of the developments in Niger on the market in August was not significant as the spot price of uranium grew from USD 56.1/lb to only USD 58.5/lb in less than a month. In early September, though, it sharply rose to above USD 60/lb and continued to climb to over USD 70/lb at the time of this writing. So, what happened?

On September 3, Cameco issued a production and market update, saying that production would drop from the previously projected 18 million to 16.3 million pounds of U3O8 at the Cigar Lake mine, and from 15 million to 14 million pounds at the McArthur River mine and associated Key Lake uranium mill. In total, production will drop from about 12,700 tonnes to 11,650 tonnes. “As mining activities continued in the west pod during the third quarter, equipment reliability issues emerged which further affected performance. The mine is scheduled to enter its planned annual maintenance shutdown that will run through most of September,” the company commented.

Even more disturbing was the comment on the McArthur River mine: “There is continued uncertainty regarding planned production in 2023 at Key Lake due to the length of time the facility was in care and maintenance, the operational changes that were implemented, availability of personnel with the necessary skills and experience, and the impact of supply chain challenges on the availability of materials and reagents. These factors have combined to impact production at Key Lake, leading to the reduced forecast.”

Ironically, it is not a Russian company burdened with commodity, monetary and logistics sanctions, but one of the world’s leading uranium miners, a Canada-based uranium supplier to European nuclear power plants (long-term contracts have recently been signed with Ukraine and Bulgaria), that is facing equipment issues and shortages of qualified personnel, chemicals and materials. And such a great company cannot straighten things out and de-mothball its flagship projects! What then can be said about other companies and mothballed facilities?

This begs the question why recognizing the problem of re-energizing uranium mines is so important.

A spokesperson for Euratom made two key points in a comment to Reuters on the situation in Niger. The first one was on the short-term situation: “If imports from Niger are being cut, there are no immediate risks to the security of nuclear power production in the short term.” The other touched upon the long-term prospects: “Medium and long-term, there are enough deposits on the world market.”

Cameco’s press release disproved the second statement. It turned out it would not be possible to quickly set up production of U3O8 at the existing mines, at least in the medium term, and there are no available reserves. This is how the situation looks like, statistically and emotionally for one, and the data and emotions are the primary factors that drive the behavior of financial investors. It should be noted that Cameco has not produced more uranium than it has sold for the last 15 years at least. The minimum gap was in 2015, with 32.4 million pounds sold and 28.4 million pounds produced. The largest gap was registered in 2020 (5 and 30.7 million pounds, respectively).

In such a situation, the most reliable solution is to enter into a long-term contract with someone who surely has uranium and faces no supply problems. That this idea is reasonable was confirmed very soon. At the very end of September, Kazatomprom announced the convening of an extraordinary shareholders’ meeting. One of the items on the agenda was the approval of a major transaction. The Kazakhstan company agreed to sell U3O8 to China’s State Nuclear Uranium Resource Development Company Limited (SNURDC). The transaction has to be approved by the shareholders because “together with the deals previously made with SNURDC, the value of this transaction is fifty percent or more of the total book value of the Company’s assets.” The first deal between Kazatomprom and SNURDC was concluded in November 2021. According to the consolidated financial statements for 1H 2023, the total assets of the company make almost KZT 2.43 trillion. Given the forecast exchange rate of KZT 470 per USD adopted by the company for 2023, its assets amount to over USD 5.16 billion. For a rough understanding of the deal’s size, we can take whatever price seems most likely to readers. We took USD 50/lb for our estimate. As a result, the supplies will be slightly less than 20,000 tonnes of uranium, which is almost 94% of the last year’s production in Kazakhstan (nearly 21,230 tonnes of uranium).

And, of course, uranium can be bought from Rosatom. The Russian nuclear corporation mines uranium in Russia (the country ranks fourth worldwide in terms of reserves) and develops uranium projects in other countries. Its production is quite stable, and there are plans to increase it both in Russia and abroad. Rosatom does not disclose information on its transactions due to the geopolitical situation, but indirect data shows that demand remains high.

What’s next?

The financial sector is most interested in whether the price of uranium will rise. Western business media say it will because governments look favorably on nuclear power. However, the authors of A Critical Disconnect: Relying on Nuclear Energy in Decarbonization Models While Excluding It from Climate Finance Taxonomies from the Center on Global Energy Policy (CGEP) at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (we wrote about this report in our previous issue) note that institutional investors either explicitly exclude nuclear power from their policies or fail to clarify the issue. Governments are the main investors in nuclear, but the USA has no money but a huge debt, as seen from the latest budget debate, and Europe’s economy is either stagnant or in recession.

So, accidents at nuclear power plants and the state of economy are the two most important factors affecting the uranium market and price. We do not discuss the former, but the latter is completely uncertain for now. In March, the World Bank released a report entitled Falling Long-Term Growth Prospects: Trends, Expectations, and Policies, in which experts promised the world’s economy would slow down to its lowest in 30 years: “Nearly all the economic forces that powered progress and prosperity over the last three decades are fading. As a result, between 2022 and 2030 average global potential GDP growth is expected to decline by roughly a third from the rate that prevailed in the first decade of this century—to 2.2% a year.” “A lost decade could be in the making for the global economy,” says Indermit Gill, the World Bank’s Chief Economist and Senior Vice President for Development Economics.

The IMF said this July that the world economy was recovering from the crises and global growth would be 3% this and next years. But a report released in early October this year notes that the fragmentation of the global economy could decrease the world GDP by from 0.2% to 12%. Such a high dispersion of figures is a lack of consensus in estimates, the IMF admits.

It is therefore easier to make a bet on what the uranium price will be by the end of the year. Checking on the New Year’s Eve whether your bet has won is at least interesting.